AP Syllabus focus:

‘Debt crises, international lending agencies like the IMF, and global finance connect economies and increase interdependence.’

Global financial crises and the institutions that respond to them shape how countries interact economically, creating deeper interdependence as financial flows, debt, and investment cross borders.

Global Financial Crises and Their Geographic Significance

Global financial crises occur when major disruptions in banking, credit, or investment systems spread across countries, producing sharp declines in economic activity and destabilizing markets. Because the world economy is increasingly connected, problems originating in one region can produce rapid spillover effects in others.

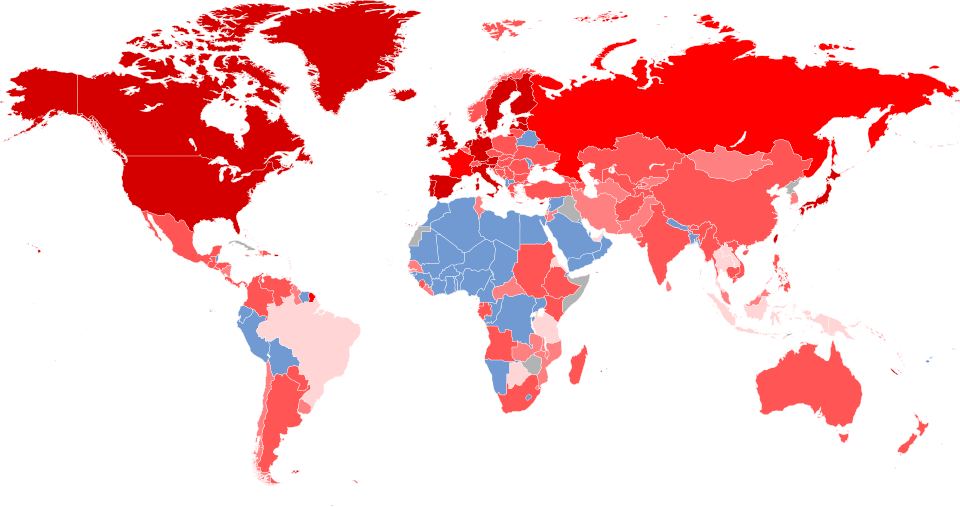

This map shows how the 2007–2009 global financial crisis affected countries worldwide, distinguishing between official recessions and varying levels of economic slowdown. It illustrates the spatial diffusion of a financial shock through interconnected economies, linking crisis impacts to global trade and financial networks. The legend includes categories of slowdown that exceed syllabus requirements but help clarify the geography of the crisis. Source.

A global financial crisis typically emerges from factors such as speculative bubbles, failures of large financial institutions, or sudden reversals of investor confidence. When these failures occur in globally influential economies, interconnected trade and financial systems transmit the shock outward. Consequences often include rising unemployment, shrinking consumer demand, currency devaluation, and tightening credit conditions in both highly developed and developing countries.

Transmission of Crisis Through Global Networks

How Crises Spread Across Borders

Because modern economies are linked through trade, foreign direct investment (FDI), banking systems, and debt relationships, financial problems in one location can rapidly expand.

Key pathways include:

Trade contraction: Countries reliant on exporting manufactured goods or raw materials face shrinking demand as global consumption falls.

Investment withdrawal: International investors may pull money out of semiperipheral and peripheral economies during crises, causing currency instability.

Banking linkages: Banks with multinational operations transmit losses across national boundaries.

Commodity price volatility: Primary-product exporters experience sudden revenue declines when global prices fall.

These linkages highlight the uneven geography of economic vulnerability, especially for states dependent on foreign capital flows.

Role of the International Monetary Fund (IMF)

Purpose and Function

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a global financial institution designed to maintain international monetary stability by providing loans, technical assistance, and policy advice to member countries experiencing economic distress.

This photograph shows the headquarters of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in Washington, D.C., symbolizing the central role of this institution in global economic governance. The building represents where decisions about emergency lending, surveillance, and policy conditionality are made during financial crises. The image includes more architectural detail than required by the syllabus but effectively anchors the concept of an international lending agency in a real-world location. Source.

International Monetary Fund (IMF): A global organization that offers financial support and policy guidance to countries facing balance-of-payments problems or economic crises.

IMF interventions are particularly significant during global financial crises. Countries suffering from currency collapse or severe debt may request IMF assistance to stabilize their economies and restore investor confidence.

The IMF typically provides:

Emergency loans to stabilize national currencies.

Structural adjustment programs (SAPs) aimed at long-term economic reform.

Monitoring and evaluation of member economies to prevent future crises.

Coordination with other lenders, such as the World Bank, during major crises.

Conditionality and Controversy

IMF loans often require borrowing countries to implement specific policies, known collectively as conditionality, which may include reducing government spending, liberalizing trade, or privatizing state-owned industries. These policies can reshape national economic landscapes, frequently affecting workers, social services, and domestic industries.

Critics argue that conditionality may:

Deepen inequality by cutting social programs.

Reduce national economic sovereignty.

Prioritize global investor stability over local development needs.

Supporters contend that SAPs encourage long-term fiscal discipline and integration into the global economy.

Debt Crises and Global Interdependence

Why Debt Crises Occur

Debt crises emerge when countries cannot repay loans due to declining export revenues, rising interest rates, or currency instability. These crises have spatial patterns: core countries are typically lenders, while semiperipheral and peripheral states are more often borrowers.

Debt Crisis: A situation in which a country cannot repay external debts, threatening its economic stability and requiring outside assistance.

Debt crises can quickly become global because lending and repayments create financial chains linking economies across continents. When large numbers of countries struggle simultaneously—often during worldwide downturns—global financial systems are disrupted.

One normal explanatory sentence fits here before the next major section begins.

Global Finance and Growing Economic Interdependence

How Financial Interdependence Works

Financial interdependence refers to the mutual reliance between economies that results from cross-border flows of money, investment, and credit.

Economic Interdependence: A condition in which countries are strongly connected through trade and financial flows, making their economic fortunes linked.

This interdependence expands as more countries participate in global capital markets.

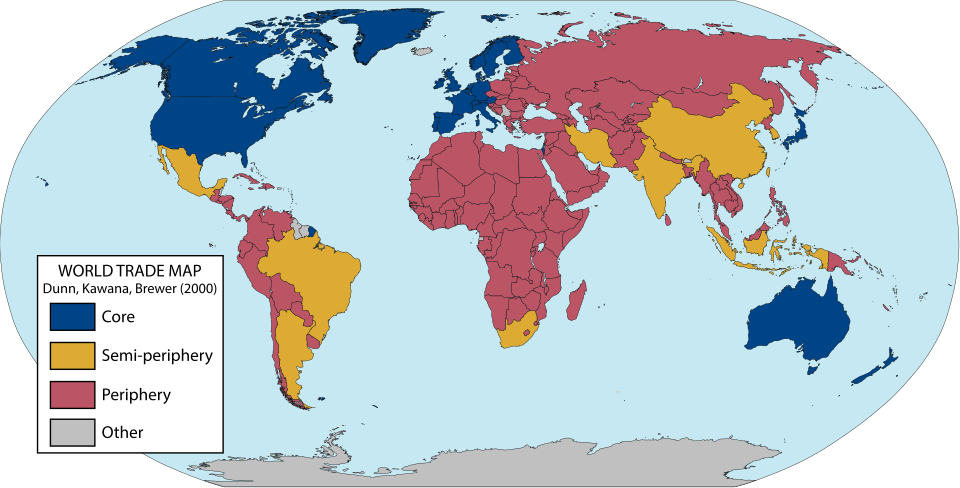

This map shows countries classified by their role in global trade as core, semiperiphery, or periphery, highlighting uneven patterns of economic connectivity. It supports the idea of interdependence by illustrating how some states dominate global networks while others are more dependent. The world-systems categories and late–20th-century context exceed the strict syllabus focus on financial crises but offer useful spatial context for global interdependence. Source.

Because financial interdependence binds economies together, global crises often have far-reaching impacts:

Faster global transmission of risk as investors move capital rapidly.

Shared economic downturns, even in countries not responsible for the original crisis.

Pressure on developing economies that depend on foreign loans or export revenues.

Coordinated global responses, including IMF interventions and multinational stimulus efforts.

Interdependence therefore makes global crises more complex but also encourages international cooperation.

Spatial Patterns of Crisis Impact

Uneven Effects Across Core, Semiperiphery, and Periphery

The consequences of global financial crises vary by development level:

Core countries often initiate or feel the crisis first due to large financial sectors, but they also have the strongest capacity for recovery.

Semiperipheral countries experience sharp fluctuations in currency values and investment flows, leading to economic instability.

Peripheral countries face declining aid, reduced commodity demand, and heightened vulnerability because their economies depend heavily on external financing.

These uneven patterns reinforce global economic hierarchies and highlight the central role of international institutions in crisis management.

FAQ

Crises often originate in core countries because they host the world’s largest financial institutions, stock markets, and investment firms. When problems such as risky lending, asset bubbles, or institutional failures occur in these hubs, the effects quickly ripple outward.

Peripheral and semiperipheral countries are more exposed because they depend heavily on trade, foreign investment, and credit from core economies, making them vulnerable to sudden financial shocks.

Developing countries often rely on exporting a narrow range of commodities or manufactured goods. When global demand falls, their earnings can decline sharply.

They may also depend on foreign loans and investment, which can be withdrawn suddenly. Limited social safety nets and smaller government budgets make it harder for these countries to cushion their populations from economic downturns.

Conditionality often involves policies designed to stabilise government finances and open economies to global markets.

Common reforms include:

Reducing public spending

Raising taxes or removing subsidies

Privatising state-owned companies

Liberalising trade and investment rules

While intended to restore long-term stability, these measures can lead to short-term social and economic hardship.

When a country’s currency loses value, its foreign debts become more expensive to repay because the loans are often denominated in stronger currencies like the US dollar.

Devaluation can also reduce purchasing power and fuel inflation, making imports more costly. While it may boost exports by making them cheaper internationally, this benefit is often outweighed by rising debt burdens during crises.

Countries attempt to build resilience through a mix of economic diversification and financial regulations.

Key strategies include:

Expanding into multiple export sectors rather than relying on one commodity

Maintaining larger foreign currency reserves

Regulating banking activities to limit risky lending

Developing social protection systems to support households during downturns

These measures cannot prevent crises but can reduce the severity of their impacts.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which global financial crises spread from one country to another.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid mechanism of transmission (e.g., reduced trade, investor withdrawal, banking linkages, falling commodity demand).

1 mark for explaining how the mechanism operates (e.g., shrinking export markets reduce revenue for other countries).

1 mark for linking this process to cross-border economic connections or interdependence.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse the role of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in responding to debt crises in developing countries.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying the basic purpose of the IMF (e.g., stabilising international monetary systems, providing emergency loans).

1 mark for describing how IMF loans support countries facing debt or balance-of-payments problems.

1 mark for explaining the concept of conditionality or structural adjustment.

1 mark for discussing one positive outcome (e.g., restored investor confidence, stabilised currency).

1 mark for discussing one criticism or negative effect (e.g., cuts to social spending, reduced national sovereignty).

1 mark for linking the IMF’s role to wider patterns of global interdependence.